Shelley Trower

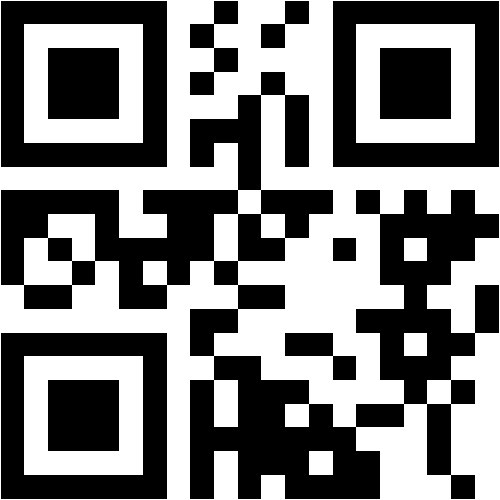

@roehampton.ac.uk

School of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences

University of Roehampton

EDUCATION

PhD in English Literature/Cultural History, Birkbeck College, University of London (awarded 2006)

MA in English Literary Research, Birkbeck College, University of London (2000)

BA English Literature, Bath Spa University (1st class) (1999)

RESEARCH INTERESTS

Life Writing, Oral History, Reading, Environmental crisis, Activism, Memory

Scopus Publications

Scopus Publications

Shelley Trower

Oxford University PressNew York

Abstract For all its orality, oral history has a long-standing, closely entwined relationship with writing. Sound Writing considers the interplay between sound recordings and written literature, looking back to antiquity while focusing on the nineteenth to the twenty-first centuries. It also refers to a dream of sound writing itself, enabling voices to reach readers directly, cutting out the need for authorial mediation. Oral histories are nevertheless actively mediated, often turned into and received as written texts. There can be value in transforming spoken oral histories in print or on screen, not least in order to make them “readable” for wider audiences. Indeed, such re-creations can be worthy and wonderful works of scholarship and art—and this book explores a wide range of different forms and media (like the polyphonic novel and hyperlinked websites) that can most effectively convey speakers’ narratives on their own terms—but there is also, always, the danger of speakers’ voices being distorted or lost in the process of mediation. This book examines how oral histories are co-created, by speakers, by authors, and also by readers. It considers how oral history can inform our understandings of authorship and reading, to reconceive and query their potential as creative, multiple, collective, and activist. Finally, it reflects on the role of authorship in the academy.

Shelley Trower

Informa UK Limited

ABSTRACT For many readers, Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings stands out as a memorable, even life-changing book. Some readers have written autobiographically about reading this autobiographical text. In this essay, I look briefly at some of this writing about reading Angelou’s book, asking how it has affected different readers in the US and UK at different moments. For many, Angelou’s representation of Black experience in the American South, and of childhood sexual abuse, is crucial. I propose that for a reader such as myself, living in the wake of the widespread discrediting of ‘recovered memories’ that emerged in the 1990s, I Know Why could serve to destabilise the boundary between uncontested childhood memories and discredited memories of abuse.

Shelley Trower

Project Muse

Shelley Trower

Palgrave Macmillan UK

Shelley Trower

Palgrave Macmillan

A. Enns and S. Trower

Palgrave Macmillan UK

Anthony Enns and Shelley Trower

Palgrave Macmillan UK

R. Hutton

Routledge

R. Hutton

Routledge

Shelley Trower

Cambridge University Press (CUP)

The final chapters of Bram Stoker's novel The Jewel of Seven Stars (1903) are set in a house on the “very verge” of a cliff in Cornwall, the peninsula located at the far south west of England. The narrator, Malcolm Ross, travels overnight from London to Cornwall, then describes his first sight of the house, and a little later the position of the dining-room, its walls hanging over the sea: We were all impressed by the house as it appeared in the bright moonlight. A great grey stone mansion of the Jacobean period; vast and spacious, standing high over the sea on the very verge of a high cliff. When we had swept round the curve of the avenue cut through the rock, and come out on the high plateau on which the house stood, the crash and murmur of waves breaking against rock far below us came with an invigorating breath of moist sea air . . .We had supper in the great dining-room on the south side, the walls of which actually hung over the sea. The murmur came up muffled, but it never ceased. As the little promontory stood well out into the sea, the northern side of the house was open; and the due north was in no way shut out by the great mass of rock, which, reared high above us, shut out the rest of the world. Far off across the bay we could see the trembling lights of the castle, and here and there along the shore the faint light of a fisher's window. For the rest the sea was a dark blue plain with here and there a flicker of light as the gleam of starlight fell on the slope of a swelling wave. (195–96; ch. 17) In this liminal place, there is a confusion of categories: the sea not only crosses the boundary into land (the sound of its “murmur” and its moistness in the air) but seems itself to become land (a “dark blue plain”). The actual land is in contrast invisible from the house, being shut out by a mass of rock that rears high above. From the far distant shore, on the other side of the bay, the lights vibrate across both land and sea, further collapsing the sense of a distinction between them: from the “trembling lights” of the castle to the intermittent “flicker of light” on the waves.

Shelley Trower

Palgrave Macmillan US

Shelley Trower

Palgrave Macmillan US

L. Salisbury and Andrew Shail

Palgrave Macmillan UK

Shelley Trower

Consortium Erudit

This essay examines how the Aeolian harp functions as a model for the workings of the human nervous system as understood in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. It sets out the scientific contexts – ranging from Hartleyan associationism to medical theories regarding the origin of life – that informed, in particular, two of Coleridge’s best-known poems: “The Aeolian Harp” and “Dejection: An Ode.” The essay provides a materialist account of mind, emphasising its inseparability from the body and physical world, as a corrective to the tendency in past criticism to overemphasize the transcendental aspect of the Romantic worldview and its attendant poetics. Further, it develops the insights of critics such as Jonathan Crary who have previously focused on optical instruments and vision by turning instead to a sonorous model for the self.